Delegation and Duration

Note 4 from the research journal by Nicklas Lundblad

Note 4

Let’s say that we stop calling agents agents, perhaps because we believe that agency is a much harder problem than has hitherto been recognized. True agency - to desire things, to want them - seems to be a deeply evolutionary quality in a system and exploring that may be its own project. We could then speak of artificial delegates instead - a much better, and arguably much clearer term. If we do, we quickly realize that the key dimensions that policy makers will be interested in are scope and duration. To what extent do you delegate, and for how long? This is how the law also thinks about delegated powers in organizations, for example, and powers to represent or act on behalf of others.

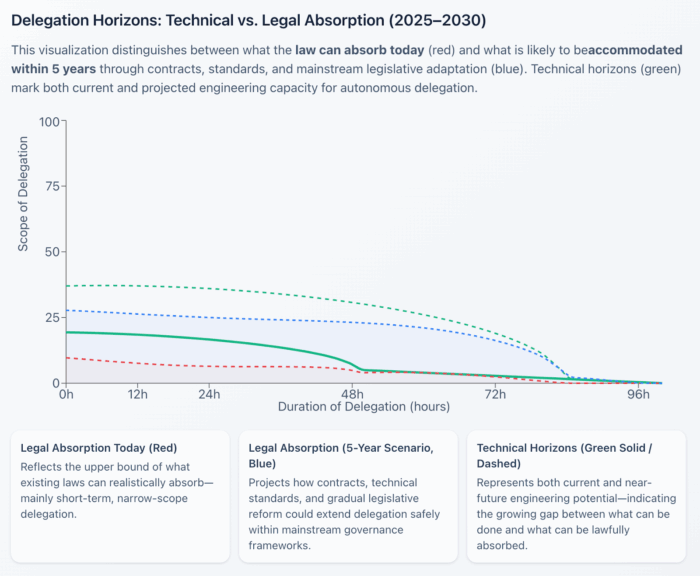

Delegation and duration can then be explored both from a technical and legal point of view: how much and for how long can we delegate today (and where do we expect to be able to go in the next 5 years?) - and is there a mismatch between what the law can absorb in terms of artificial delegation now, and with predictable evolution of contracts and standards? We can use this mental model to state assumptions and discuss implications of artificial delegates in different ways. Here is an example of the model:

In this analysis, today’s delegation allows for slightly more than what law can accommodate or absorb, but there is also a prediction of a growing legal absorption capacity. However, the technical capacity seems to be growing faster in the next 5 years than the law, creating a regulatory gap that needs to be explored and dealt with.

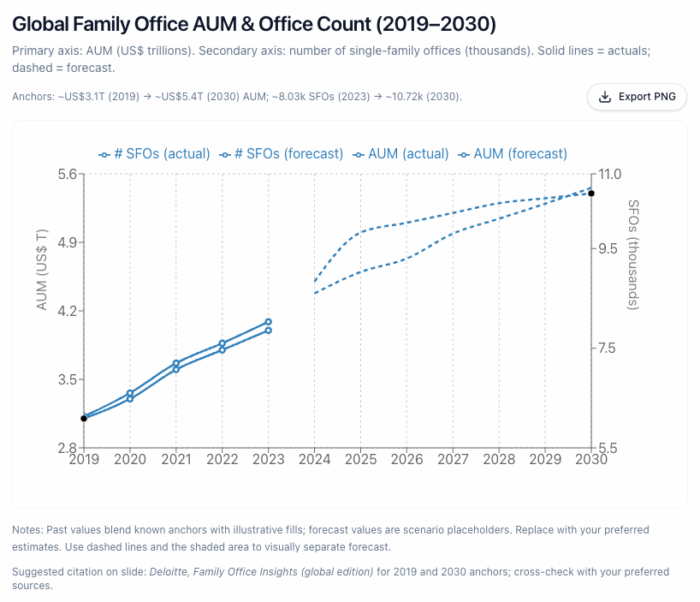

The changes and evolutions of law here are gradual and incremental - but we should also recognize that there are combinations of delegation and duration that current law is not that good at accommodating. An example of that would be delegates that can act over very long periods of time - say centuries - in the interest of an individual’s lineage. Such entities are already known to law - family trusts - and it is far from impossible to imagine future scenarios in which such trusts are managed not by individuals or trustees, but by artificial intelligences. They have a limited remit: they are to act on behalf of the family’s interests in managing wealth and real estate, say, but they can have a nearly infinite mandate. This might seem a hypothetical example, but the trend today is for more and more wealthy people to put their money in family offices of different kinds. Private family offices are prime candidates for such narrow, long term delegation:

Family trusts then, could easily develop into long term delegates with almost infinite mandates. We could also imagine charitable trusts and NGOs setting up similar structures. The question is if we should allow that, or if it is sound policy to limit the duration of any delegation to an artificial entity of some kind.

One argument for such limitations is that lingering delegation may create compounding effects in a society, skewing it in ways that serve the narrow scope of the delegations rather than inspiring long term dynamism. There is already a worry that trust-ensconced wealth may have conserving effects on the economy as very risk averse long term strategies could funnel money into safer investments like index funds, bonds or similar. An economy of delegates with very long horizons is probably going to be very different from today’s economy - and in fact, you could - if somewhat morbidly - argue that today’s economy actually derives a lot of its dynamics from the fact that its participants are finite and limited in duration (well, we die…).

On the other axes, you may want to limit the scope of delegation as well – but that is less clear. There are simple value driven and normative limits that probably will remain in place for a long time: we do not want to delegate the ability to marry or adopt, for example. We probably are also going to want to think about whether to limit certain kinds of decisions - like founding a company or standing for political office. Those are human prerogatives under our current understanding of our role in society.

For the research project, I think the key take away is this: if we say that we are not going to talk about “agents” as long as what we build does not have agency, then the framing of delegation, and the dimensions of duration and scope are actually helpful to think through policy and legislative challenges.