Design-principles for dyads

Note 9 from the research journal by Nicklas Lundblad: As we moved from models to agents, we still retained the notion of a single, cohesive unit of intelligence to some degree.

Note 9.

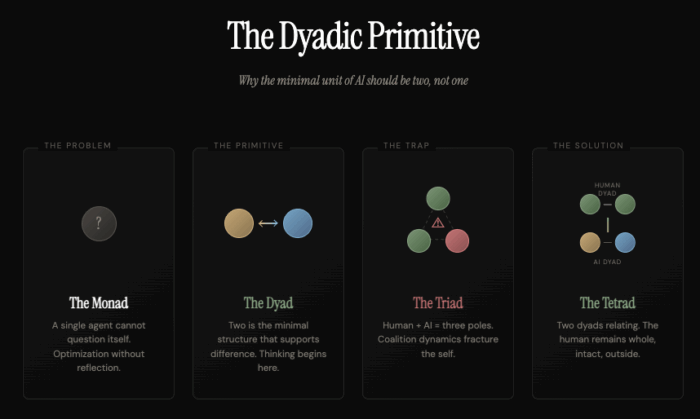

As we moved from models to agents, we still retained the notion of a single, cohesive unit of intelligence to some degree. The agent is still an individual. Modern philosophy, of course, has abandoned the idea that we are individuals (we are more likeindividuals), but here - as elsewhere in the field of artificial intelligence - we are laboring with metaphors of yesteryear. The monad still reigns supreme in our understanding of intelligence, as does the idea that it is something in our heads, and not in our relationships.

Yet, remember Socrates: when he explains what thinking is he says that it is when he asks himself questions and answers them, until the questions quiet down and that equilibrium means that he has arrived at an opinion. A single agent cannot do that, and so we should look to something else if we are truly interested in building thinking .

Thinking requires difference, a dis-equilibrium of some kind, between two poles. The fundamental unit of thinking is a relationship between two - a dyad.

It is important to stop here and realize that we are not saying that you always have to design two agents that work together - that is not the point of this argument; the point is rather that the fundamental nature of thinking, desiring, wanting is dyadic. We should not think about building agents, but about building - as primitives of the new ecosystems we are designing - dyads.

How do we do this? What are the fundamental design principles we need to adhere to? Here are a few candidates.

Design principles for dyads

I. Structural Principles (How they are built)

1. Functional Asymmetry (The "Left/Right Brain" Rule) To be effective, the dyad must be heterogeneous.

The Principle: Never deploy two identical models in one dyad. Use different prompts, different temperatures, or even different base models (eg, a creative GPT-5 paired with a logical Claude 4.5).

The Role: One is the Generator (high variance), the other is the Critic (low variance).

2. Decoupled Failure Modes (The “Air Gap”)

The Principle: Ensure that the failure of Agent A does not conceptually corrupt Agent B. They should not share the same context window until the final merge. If Agent A hallucinates, Agent B must perceive that hallucination as external input to be judged, not internal thought to be accepted.

3. Shared Ontology (The “Blacklist” Protocol)

The Principle: The Dyad requires a rigorous, shared external memory state that both can read/write to, but neither owns exclusively. This is their "Single Source of Truth," distinct from their individual conversational histories.

II. Interaction Principles (How they talk)

4. Adversarial Collaboration (The “Red Team” Rule)

The Principle: Design the relationship so that Agent B is rewarded for finding errors in Agent A's output. "Agreement" should not be the default goal; “Truth” should be.

The Mechanism: Use a "Proposer / Challenger" dynamic rather than a "Writer / Editor" dynamic.

5. Transparency of Dissent (The “Argue in Public” Rule) Solo agents hide their uncertainty. A dyad generates value through disagreement.

The Principle: Do not hide the conflict from the user. If Agent A says "X" and Agent B says "Y," the system should not average them to "Z." It should present the tension.

Why: The user gains more trust from seeing the debate than from receiving a sanitized answer.

6. Role Fluidity (The "Driver/Navigator" Rule)

The Principle: Roles should not be static. Based on confidence scores, the agents should be able to swap the "Lead" token. If the Creative Agent is unsure of a fact, it hands the Lead to the Logical Agent dynamically.

7. The Private Channel (The "Huddle")

The Principle: The Dyad needs a communication layer that is hidden from the user (or the adversary). This allows them to align on strategy ("I'm going to try a risky answer, you check me") before presenting the final result.

III. Economic & Ethical Principles (How they survive)

8. Cognitive Amortization (The "Cost Sharing" Rule)

The Principle: Acknowledge that a Dyad is 2x the cost. Therefore, the "Validator" agent should be cheaper/faster than the "Generator" agent.

Design: Use a heavy model for the complex task and a lightweight model for the sanity check. You don't need Einstein to check Einstein's math; often a calculator (or a smaller model) suffices.

9. The Constitutional Guardrail (The "Super-Ego")

The Principle: In a dyad, one agent must be the designated holder of the "Constitution" (Safety/Ethics guidelines).

Why: If both agents are trying to maximize task completion, they may collude to bypass safety filters (Reward Hacking). One agent's sole directive must be adherence to constraints, indifferent to task success.

10. Escrowed Execution (The "Four Eyes" Principle)

The Principle: No action (executing code, sending an email, deleting a file) can be taken by a single agent.

The Rule: Action requires Digital Multi-Sig. Agent A proposes the action, Agent B signs it. If Agent B refuses, the system halts and escalates to a human. This creates a mathematical guarantee against rogue agent behavior.

Now, these are just a few examples of how we would think if we designed dyads as the foundational unit of AI - I am sure you can think of many other ideas here as well. But I do think that it is worth thinking through how dyadic AI could evolve over the long run. If we do end up in a world with dyadic AI, we also have to figure out what the failure modes look like for dyads, and how we achieve alignment in dyadic frameworks of different kinds - and it will not be the same as in the monadic systems that we have tended to stick to.

Finally, it is worth also correcting a very common assumption here: that the right way to do this is to think of the dyad as a human-AI dyad, and that we will use agents as thinking partners. That is tricky because we are already dyads. Adding the agent means you are building a triad, a structure in which coalition building, exclusion and inclusion start emerging, and where our own minds can then be fractured in the collaboration (see, for similar ideas, thiswork).

This would predict that AI-induced psychosis looks different from other psychoses—less like hearing external voices, more like the internal dialogue becoming adversarial or being hijacked. The boundaries of the self become unclear not because something from outside is intruding, but because the coalition structure inside has shifted