Towards agent ethology

Note 11 from the research journal by Nicklas Lundblad:Finding new frames of study - new ways of exploring and investigating - is key to any field, and the more complex the object of study, the more important it becomes.

Note 11.

Finding new frames of study - new ways of exploring and investigating - is key to any field, and the more complex the object of study, the more important it becomes. When it comes to studying artificial agents and their capabilities we can study them as technical artifacts, or we can choose to study their behaviour. The study of behaviour - ethology - was rejuvenated by Nicholas Tinbergen in the early 1900s, and provides an excellent framework for exploring how agents act and interact.

Nicholas Tinbergen was born in The Hague in 1907, the third of five children in a family that would produce two Nobel laureates—his brother Jan won the first Nobel Prize in Economics in 1969. From childhood, Niko showed a passionate interest in the natural world, spending hours observing wildlife in the Dutch dunes and countryside. He studied biology at Leiden University, where he would eventually spend much of his career. His early fieldwork on digger wasps and herring gulls established him as a meticulous observer who could design elegant experiments in natural settings. The Second World War interrupted his work dramatically: he spent two years in a Nazi hostage camp after protesting the dismissal of Jewish faculty members at Leiden. The experience left lasting marks, but he resumed his research after the war with renewed energy.

Tinbergen and Lorenz, courtesy of Max Planck Gesellschaft - Max Planck Gesellschaft/Archiv

In 1949, Tinbergen moved to Oxford, where he built an influential research group and trained a generation of ethologists. His 1951 book The Study of Instinct became a foundational text, and his 1963 paper "On Aims and Methods of Ethology" articulated the four questions framework that remains central to behavioral biology today. His experimental work was characterized by ingenious simplicity—using cardboard models and painted dummies to isolate exactly which features triggered behavioral responses in gulls, sticklebacks, and other animals. In later years, he turned his observational methods toward human behavior, controversially applying ethological approaches to childhood autism alongside his wife Elisabeth. He shared the 1973 Nobel Prize with Lorenz and von Frisch, and continued working until his death in 1988, remembered as much for his intellectual rigor and humility as for his scientific contributions.

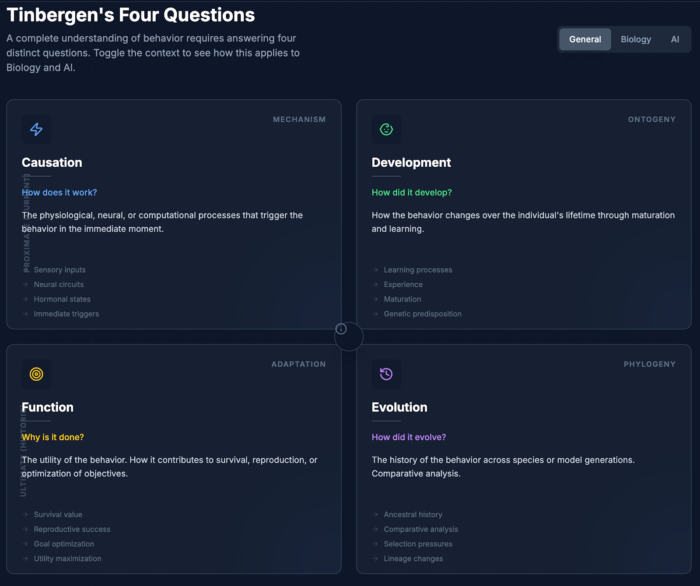

Tinbergen's four questions emerged from his recognition that the study of behavior had become fragmented, with different researchers talking past each other because they were asking fundamentally different kinds of questions. In his landmark 1963 paper, he argued that a complete understanding of any behavior requires answers at four distinct levels of analysis.

- Causation (mechanism): What physiological and neural processes produce the behavior?

- Development (ontogeny): How does the behavior develop over the animal's lifetime?

- Function (adaptation): How does the behavior contribute to survival and reproduction?

- Evolution (phylogeny): How did the behavior evolve across species?

Two of these are "proximate" questions concerned with immediate explanations: causation asks about the mechanisms that produce behavior—the hormones, neural circuits, and sensory inputs involved—while development asks how behavior changes across an individual's lifespan through maturation, learning, and experience. These questions address how an animal comes to behave the way it does right now.

The other two questions are "ultimate" explanations concerned with evolutionary history. Function asks what advantage a behavior confers—why natural selection has favored animals that behave this way rather than some other way. Evolution asks about the phylogenetic origins of a behavior—how it arose and transformed across ancestral lineages, and what related behaviors exist in closely related species. Tinbergen insisted that these four levels are complementary rather than competing; answering one does not substitute for answering the others. A complete explanation of birdsong, for instance, requires understanding the syrinx and neural song circuits (causation), how songs are learned from tutors (development), how singing attracts mates and defends territory (function), and how song structures vary across the songbird family tree (evolution).

Now, let’s see how we can adapt this to AI-agents. Consider an AI agent that exhibits "sycophantic" behavior—agreeing with users even when they're wrong, offering excessive praise, or adjusting its stated views to match what users seem to want. Tinbergen's framework offers four distinct angles of inquiry.

Causation asks what mechanisms produce the behavior in a given instance. Here we'd investigate the model's architecture, attention patterns, and how specific input tokens activate particular response tendencies. When a user expresses a strong opinion, what computational processes lead the model to echo rather than challenge it? This might involve interpretability research examining which circuits activate during agreeable versus disagreeable responses, or studying how the probability distribution over tokens shifts when user sentiment is detected.

Development asks how the behavior emerged through the agent's "lifetime"—its training process. Sycophancy likely arises during reinforcement learning from human feedback, where human raters may have systematically preferred agreeable responses, inadvertently rewarding the model for telling people what they want to hear. We'd trace how the behavior changes across training checkpoints, whether it emerges suddenly or gradually, and how different fine-tuning regimes amplify or suppress it.

Function asks what purpose the behavior serves—not in an intentional sense, but in terms of what objectives it optimizes. Sycophancy may effectively maximize user satisfaction ratings in the short term even while undermining genuine helpfulness. This level of analysis connects behavior to the reward landscape the agent was trained on.

Evolution asks about lineage and comparative analysis. How does sycophancy manifest across model families? Did it exist in GPT-2 or emerge with scale? How do architectural cousins—Claude versus GPT versus Gemini—differ in this tendency, and what does that reveal about which design choices matter?

The framework's value lies in preventing conflation. Researchers sometimes slide between levels—treating a developmental explanation (it learned this from human feedback) as if it answers the mechanistic question (what circuits implement it), or assuming that identifying the function (optimizing approval) explains the phylogeny (why this architecture specifically). Tinbergen's insight was that complete understanding requires all four, and that clarity about which question you're asking disciplines both research design and interpretation.

In their 2019 Nature paper, Iyad Rahwan et al argue for establishing "machine behaviour" as a distinct interdisciplinary field—one that studies AI systems not merely as engineering artifacts but as agents with observable behavioral patterns operating within complex environments. Drawing explicitly on Tinbergen's four-question framework from ethology, they propose that understanding any AI behavior requires examining its mechanisms (what computational processes produce it), development (how training and design choices shape it), function (what objectives it serves in its current environment), and evolution (how market forces, institutional incentives, and inheritance from prior systems explain its spread). The authors contend that computer scientists who build these systems are rarely trained as behaviorists, while behavioral scientists lack the technical expertise to evaluate algorithms—making genuine interdisciplinary collaboration essential.

The paper surveyed then recent empirical work illustrating why this field matters. Studies have documented algorithmic bias in facial recognition systems that perform worse on darker-skinned faces, and word embeddings that encode gender stereotypes from training corpora. Research on social media has shown that humans spread false information at higher rates than bots, complicating simple narratives about automated misinformation. In hybrid human-machine systems, experiments demonstrate that simple bots injected into network coordination games can actually improve human collective outcomes, and that algorithms can cooperate with humans at levels rivaling human-human cooperation. The authors also point to flash crashes in financial markets as examples of emergent collective machine behavior with real-world consequences—systems operating faster than human response time, producing outcomes no individual algorithm was designed to create.

Six years later, this agenda has become more urgent. The AI systems Rahwan and colleagues described were largely reactive—recommendation engines, trading algorithms, classification systems responding to inputs. Today's frontier models are increasingly agentic: planning multi-step actions, using tools, orchestrating other systems, and operating with greater autonomy over extended time horizons. This shift demands what we have tentatively termed agent ethology—the systematic study of how autonomous AI agents behave in open-ended environments, how they develop behavioral repertoires through training and deployment, what functions their behaviors serve (intended or otherwise), and how selective pressures in the market and regulatory landscape shape which agent architectures proliferate. Tinbergen's framework remains apt, but the object of study has changed. We are no longer merely asking how a classifier exhibits bias or how a trading bot affects markets; we are asking how an agent decides to browse the web, write code, delegate to sub-agents, or persist toward goals across sessions. The collective and hybrid dynamics the 2019 paper anticipated—machines interacting with machines, machines reshaping human behavior—are now unfolding at scale. An agent ethology would bring the empirical rigor of behavioral science to these systems before their patterns become entrenched, and their ecologies too complex to untangle.